How can craft practice in digital lutherie be supported and augmented?

This PhD, being investigated by Jack Armitage, aims to contribute to understanding the impact of digital lutherie tools, methods and materials on craft practice, and to propose different approaches that support the development of craft practice.

Stop the press! Participate in an upcoming study:

Are you a “luthier”, traditional, digital or otherwise? Are you interested in participating in a hands-on study about digital instrument craft? If so, contact j.d.k.armitage@qmul.ac.uk for details.

While instrument making is an artistic practice as old as all human culture, each luthier’s contemporary environment poses unique challenges and opportunities for enabling deeply meaningful musical performance and artistry. Today, “digital luthiers” design instruments using computational tools and materials which, being adapted from science and engineering, are poorly suited for master craftswork. These tools and materials do not cater for luthiers’ artistic needs, nor do they privilege and exploit the luthiers’ own body and senses as a profound set of capabilities for reading and manipulating the world. This thesis explores how technologies designed for luthiers can be rethought to suit their needs as craft practitioners, and enable them to use their entire bodies to craft great digital musical instruments in fine detail.

This summary article describes four research themes and related studies and publications:

- Comparing traditional and digital lutherie

- Exploring physical craft in digital lutherie

- Comparing physical and digital craft

- Exploring digital handcraft in digital lutherie

Want to stay up to date with this research? Join the mailing list and visit jackarmitage.com.

Comparing traditional and digital lutherie

A significant difference between traditional and digital forms of lutherie is how process knowledge is created and disseminated. In digital lutherie research, at conference venues such as New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME), emphasis is placed on generalised technical literature. This is evident in the multitude of design frameworks proposed in the literature, which aim to distill researchers’ practices into principles and guidelines for others to follow in order to succeed as luthiers. Contrast this with violin lutherie, where the inverse is true; detailed methods for achieving specific looks, feels and sounds are celebrated.

NIME frameworks are valuable for taxonomical analysis and comparison of outcomes, but less so for guiding practice. To illustrate this idea, consider two violins as an example: a Stradivarius and a factory-made student violin. According to most taxonomies these instruments are nearly identical in size, interaction mode, controls, mapping, and pitch range. Nonetheless, nuances in sound and tactile response will result in vastly different experiences for professional violinists.

Just as master luthiers possess years of accumulated knowledge in crafting fine violins, many experienced electronic instrument designers in NIME and in industry have developed detailed personal practices to produce highly-refined instruments. Some have shared personal reflections on their design practices in papers or interviews. However, research papers at NIME and similar venues do not provide a full account of craft knowledge. Some aspects of craft are personal, subjective and inherently nonscientific; other aspects, like the tacit knowledge of a master craftsperson, may not be fully communicable in writing at all.

To investigate this dilemma, we introduce the neologism NIMEcraft to describe a subset of craft that focuses on micro scale details, because we believe this is where important knowledge about digital lutherie is hiding in plain sight, assumed but unspoken.

NIMEcraft:

The micro scale differences between otherwise identical instruments and their underlying design processes.

NIMEcraft is the difference between two nominally identical reacTables, two Magnetic Resonator Pianos or two Linnstruments. Finding this comparison between traditional and digital lutherie fruitful for discussion and reflection, we interviewed violin luthiers about their craft practice in order to shed more light on the differences and similarities. The outcome provides a compelling account of how digital lutherie practice and research can use traditional lutherie as a model for understanding how to better support craft practice.

Read the research article:

J. Armitage, F. Morreale and A. McPherson. “The finer the musician, the smaller the details”: NIMEcraft under the microscope. Proc. New Instruments for Musical Expression, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. Download PDF

Exploring physical craft in digital lutherie

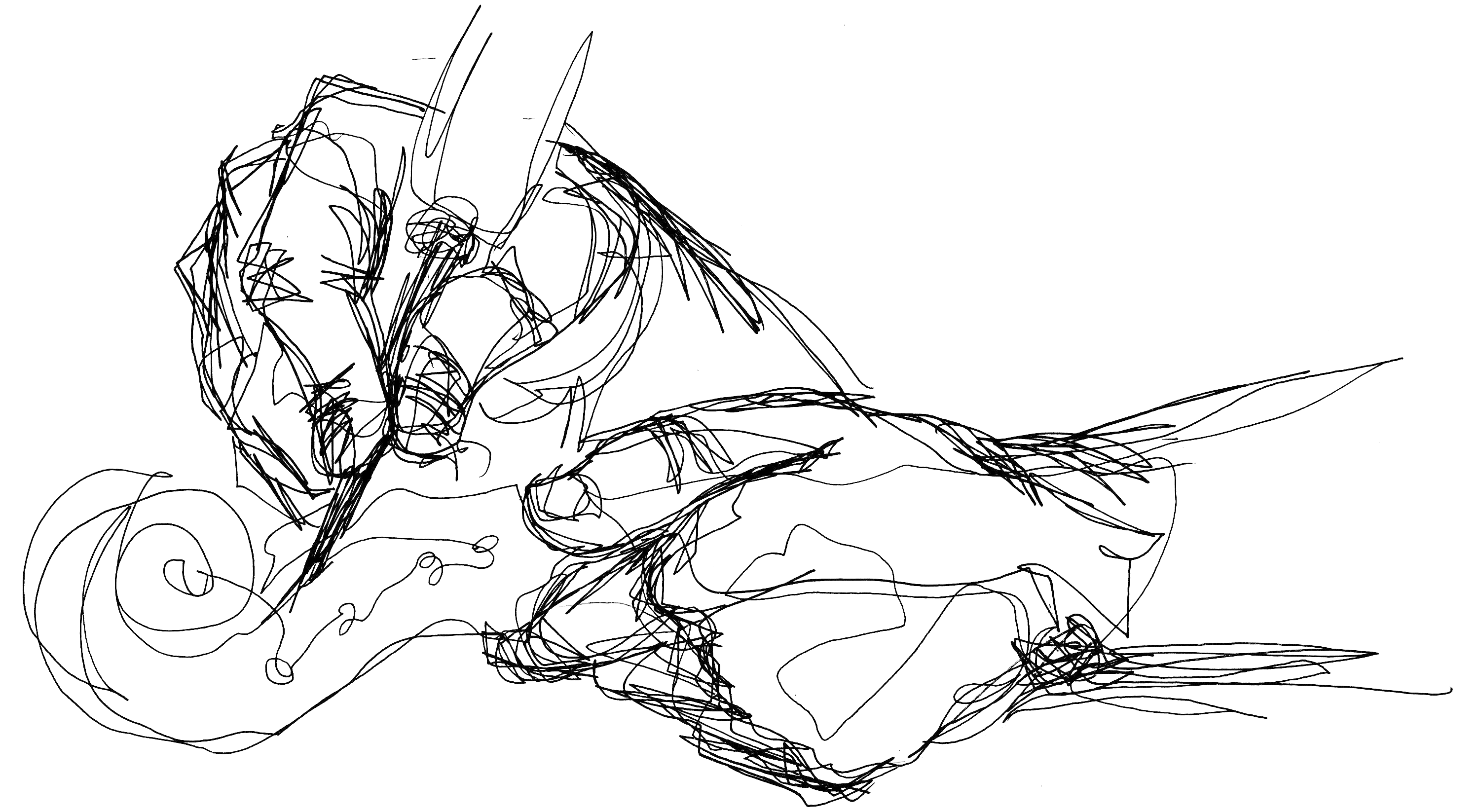

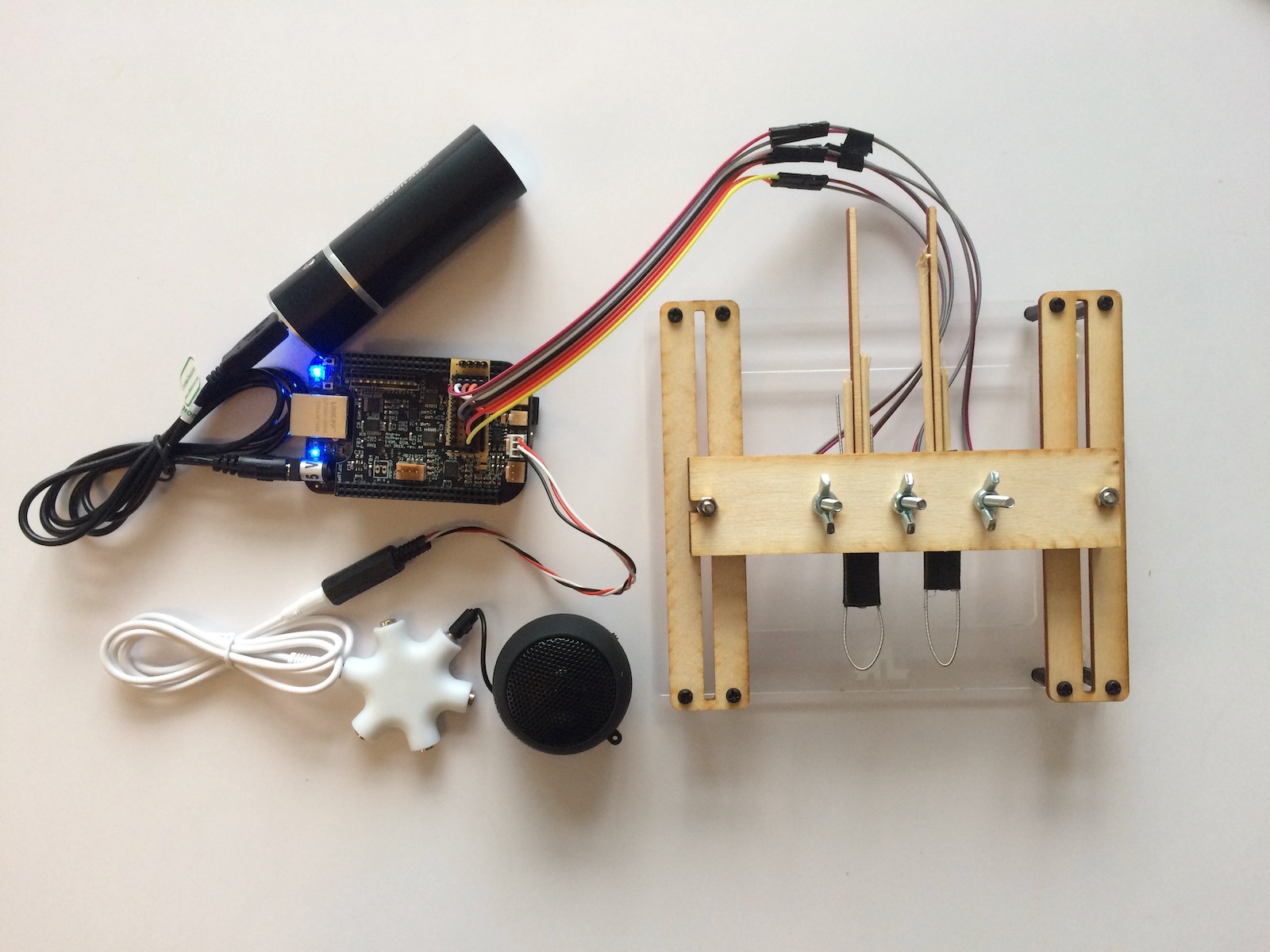

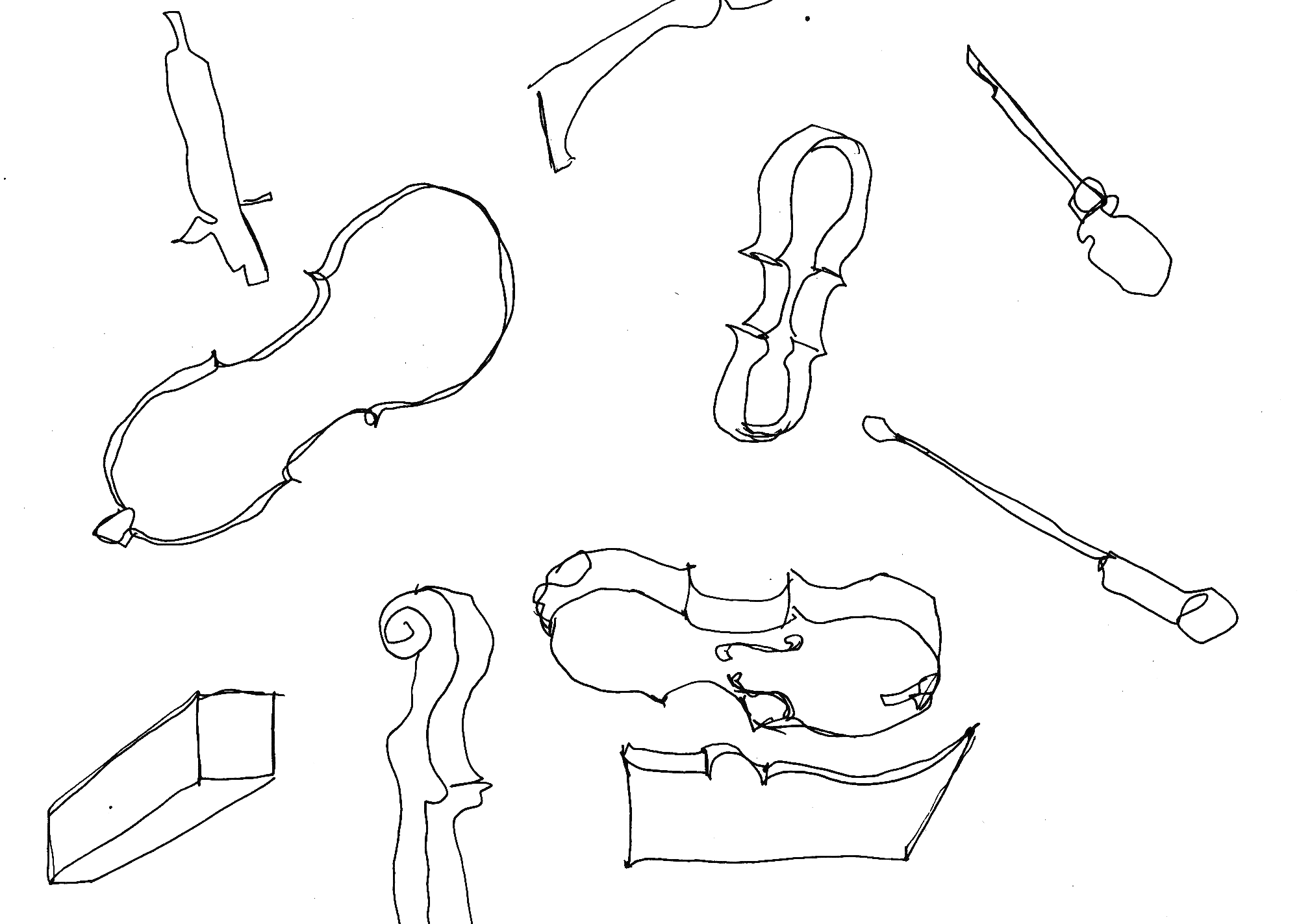

In digital lutherie, different tools and methods offer a variety of approaches for constraining the exploration of musical gestures and sounds. Toolkits made of modular components usefully constrain exploration towards simple, quick and functional combinations, and methods such as sketching and model-making alternatively allow imagination and narrative to guide exploration. In this work we sought to investigate a context where these approaches to exploration were combined. We designed a craft workshop for 20 musical instrument designers, where groups were given the same partly-finished instrument (named the Unfinished Instrument, below) to craft for one hour with raw materials, and though the task was open ended, they were prompted to focus on subtle details that might distinguish their instruments.

Despite the prompt the groups diverged dramatically in intent and style, and generated gestural language rapidly and flexibly. By the end, each group had developed a distinctive approach to constraint, exploratory style, collaboration and interpretation of the instrument and workshop materials.

In our paper we reflect on this outcome to discuss advantages and disadvantages to integrating digital musical instrument design tools and methods, and how to further investigate and extend this approach.

Read the research article:

J. Armitage, A. McPherson. Crafting Digital Musical Instruments: An Exploratory Workshop Study. Proc. New Interfaces for Musical Expression, Blacksburg, Virginia, USA. 2018. Download PDF

Comparing physical and digital craft

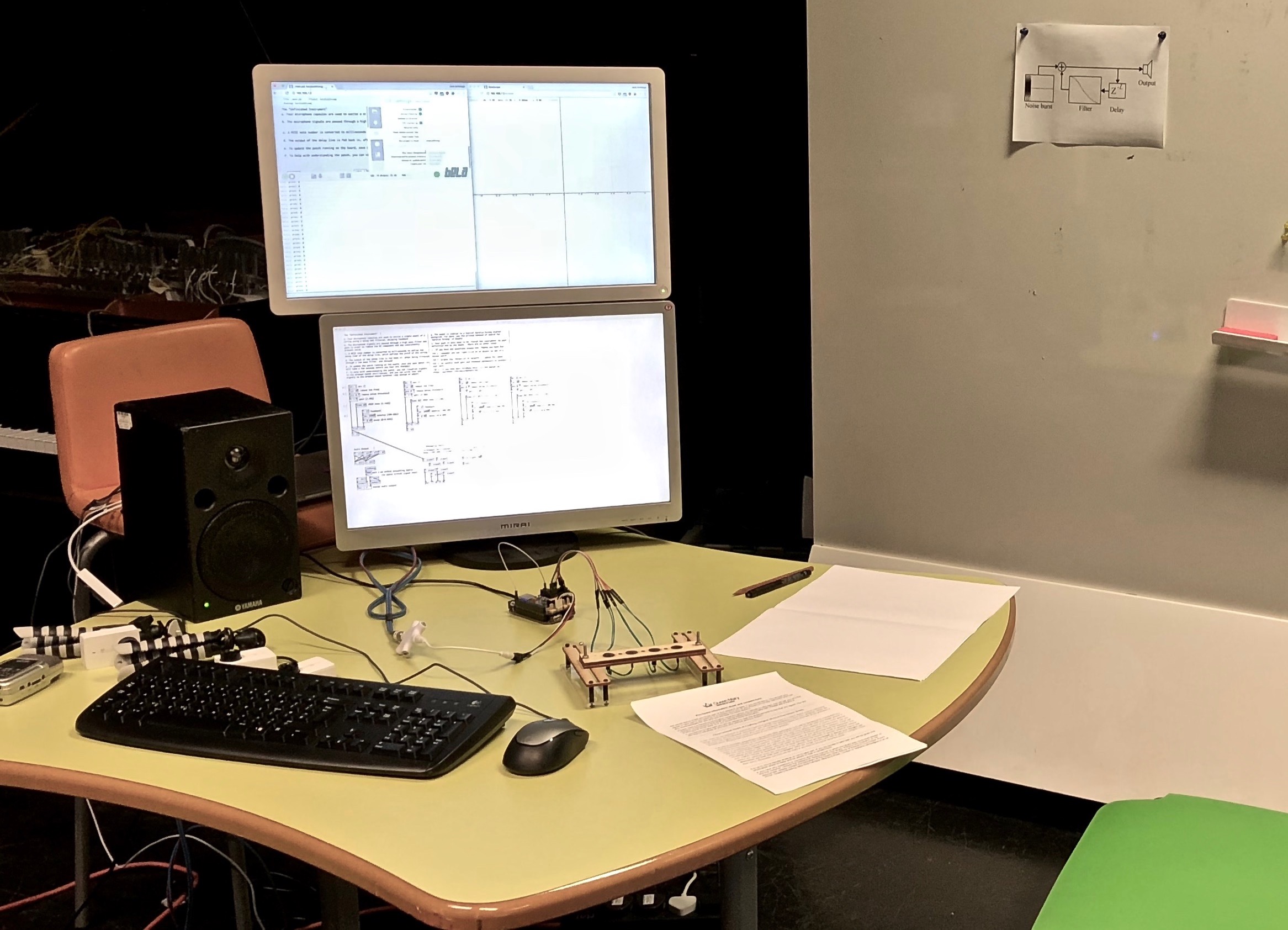

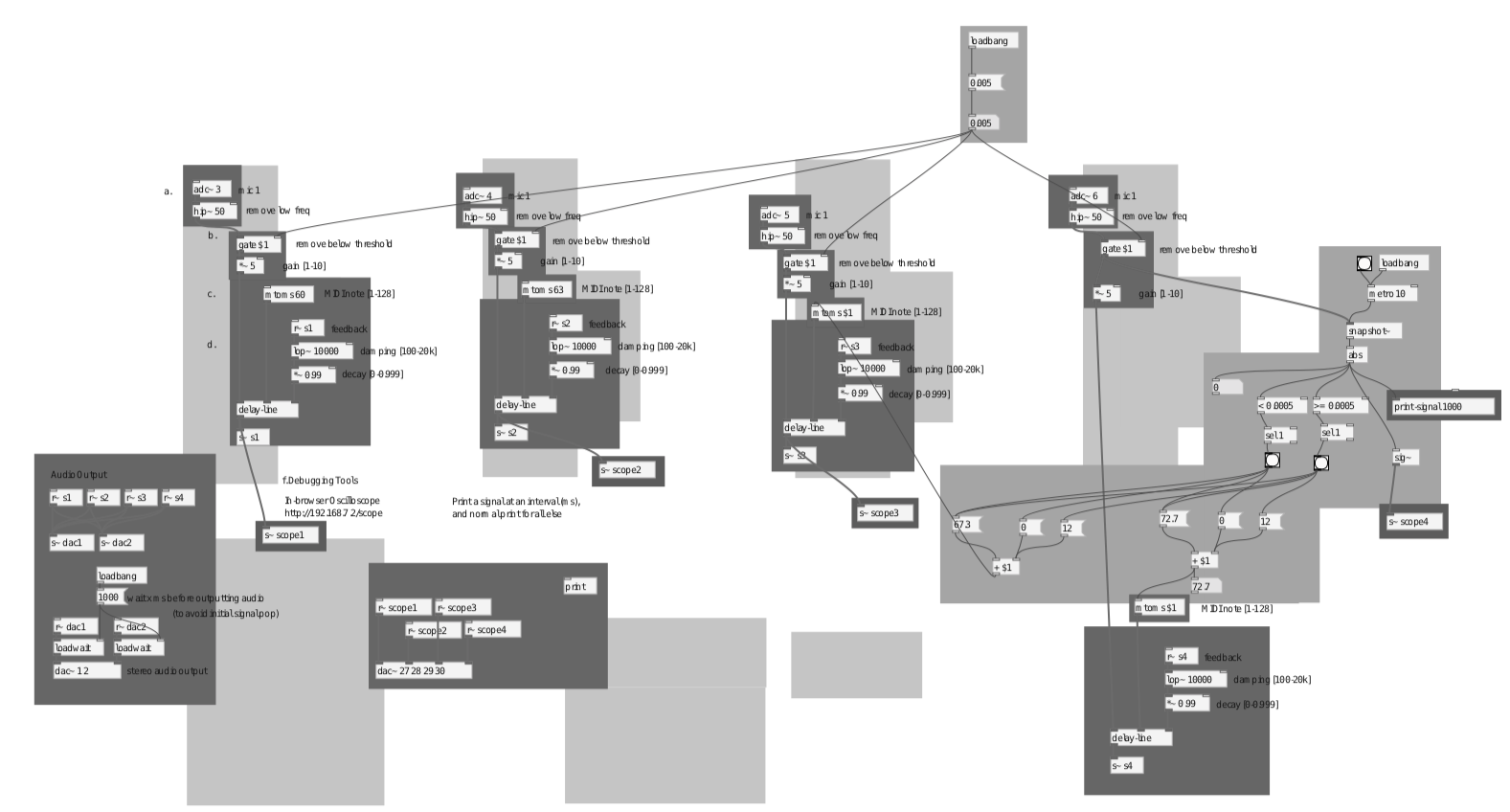

During the evaluation of the study described above, the question arose of how differently digital luthiers would approach the same task when instead working with digital rather than physical materials. Despite that digital musical instruments (DMIs) seek to facilitate embodied gestural interaction, many common DMI design tools limit the designers’ embodiment, and it is unclear how this affects the exploration and craft of musical interactions. The most common digital lutherie tools are textual and graphical programming interfaces, which create an indirect relationship between the designer and the instrument. We modified the previous craft workshop and invited 15 digital luthiers to craft for one hour with a digital material (PureData), where they were similarly encouraged to focus on adding subtlety or nuance to the gestural input or modifying the timbral response.

Overall the groups felt that they did not have enough time, and that the digital materials presented significant challenges for rapidly testing and evaluating their ideas. In a future publication we will aim to provide a commentary on the issues digital materials present for the craft practice of digital luthiers, and how technologists might be able to help.

Read the research abstract:

J. Armitage. Supporting Live Craft Process in Digital Musical Instrument Design. Proc. International Conference on Live Interfaces, Porto, Portugal, 2018. Download PDF

Exploring digital handcraft in digital lutherie

Tangible and dynamic programming interfaces have been developed to enable digital luthiers to use their haptic, tactile and spatial skills in designing musical instruments. However, they are frequently presented as pre-defined components and finished products, which constrain open and subjective exploration and crafting processes. Electronic paper and textile materials, while being more open to handcrafting, are often suggested as inputs and outputs to digital systems only, and do not enable the direct manipulation of program parameters, mappings and structures.

In this study, we propose to design handcrafting tools for digital luthiers that combine elements of tangible programming interfaces and digital craft materials. A group of digital luthiers will be introduced to a digital musical instrument and a handcrafting tool, and perform activities for crafting micro scale details of the instrument using the tool. The luthiers will then engage in a workshop with digital musical instrument performers, where they use their digital handcrafting skills to develop the micro scale details further. We aim to show that digital handcrafting tools provide an improved means for digital luthiers to engage in the craft of micro scale details of digital musical instruments.

Participate in an upcoming study:

Are you a “luthier”, traditional, digital or otherwise? Are you interested in participating in a hands-on study about digital instrument craft? If so, contact j.d.k.armitage@qmul.ac.uk for details.

Want to stay up to date with this research? Join the mailing list and visit jackarmitage.com.

Collected references

J. Armitage, A. McPherson. Crafting Digital Musical Instruments: An Exploratory Workshop Study. Proc. New Interfaces for Musical Expression, Blacksburg, Virginia, USA. 2018. Download PDF

J. Armitage. Supporting Live Craft Process in Digital Musical Instrument Design. Proc. International Conference on Live Interfaces, Porto, Portugal, 2018. Download PDF

J. Armitage, F. Morreale and A. McPherson. “The finer the musician, the smaller the details”: NIMEcraft under the microscope. Proc. New Instruments for Musical Expression, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. Download PDF

A. McPherson, J. Armitage, A. Bin, F. Morreale, R. Jack. NIMEcraft Workshop: Exploring the Subtleties of Digital Lutherie. Proc. New Instruments for Musical Expression, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. GitHub Repository