What is procedural audio?

Interactive environments and games still largely depend on the use of pre-recorded assets to create a dynamically changing soundscape. In recent years, thanks to the growing capabilities of consumer processors coupled with the accessibility to low-entry-fee audio programming software such as PureData and SuperCollider, procedurally generated audio is rapidly becoming a feasible alternative. Procedural methods provide the user with varying and believable sonic feedback based on their interactions with the virtual environment while potentially increasing efficiency in comparison to conventional sample-based approaches. Many scholars and professional sound designers envision the future of interactive audio (particularly game audio) to veer towards procedural generation, drawing parallels to the stage that 3D graphics were at in their infancy.

Towards expressive procedural audio

Currently, the use of procedural audio in commercial products is limited to a small set of sounds such as impacts and static ambiences. On one hand this is because they are easy to model using established physically-informed methods. On the other hand they are easy to implement in a virtual environment as they use a very small set of static parameters that don’t vary in time. Computational generation of more complex and interactive sounds (for example water splashes, car engines and door creaks) present unprecedented challenges to the sound designer. Such sound models are typically controlled by a multitude of time-varying parameters and the visual part of the environment will often not provide enough information to drive each one of these in a physically coherent way. Furthermore, perfect correlation between what is seen and what is heard is often not desirable from an aesthetic point of view – this is signified in the routine use of Foley artists in the film industry to synchronize sounds to the image (the same paradigm applies to field recording techniques and choice of samples in game audio design). It is possible to design individual sounds by programming sequences of parameter changes over time, however the immediacy that is central to performance is lost when taking this approach. Therefore a new means of interaction is investigated in this research project, centred around the exploration and performance of synthetic environmental sound.

Research areas

On a general level this research seeks to understand how expressive performance can be integrated into the process of working with procedurally generated sound. More specifically, this question encapsulates the following key areas of research:

Structure and parameterisation of the model – is a model designed for expressive performance different from conventional physically-informed models? Are parameters based on the physical behaviour of the object less conducive to performance? Mapping between physical controller and sound model – given controller X and sound model Y, what is the best way of mapping X’s output data to Y’s parameters? What approach to mapping gives the user the highest degree of control while maintaining the ability to produce effective and believable sounds? Tangibility of interface and relationship between familiar gestures and sound – is a sound best performed by interacting with its corresponding physical source, or are other physical objects more conducive performance? How important is tangibility in designing sonic behaviours? Implementation of performed sound into interactive scenarios – how are sounds implemented into the interactive scenario? Can they be synchronised in real-time or is a separate set of tools required to ‘blend’ between performed trajectories? What parallels can be drawn to procedural animation techniques?

Answering these questions brings us closer to a position where procedural audio is used as a highly expressive and malleable material rather than just a means of producing physically accurate sounds.

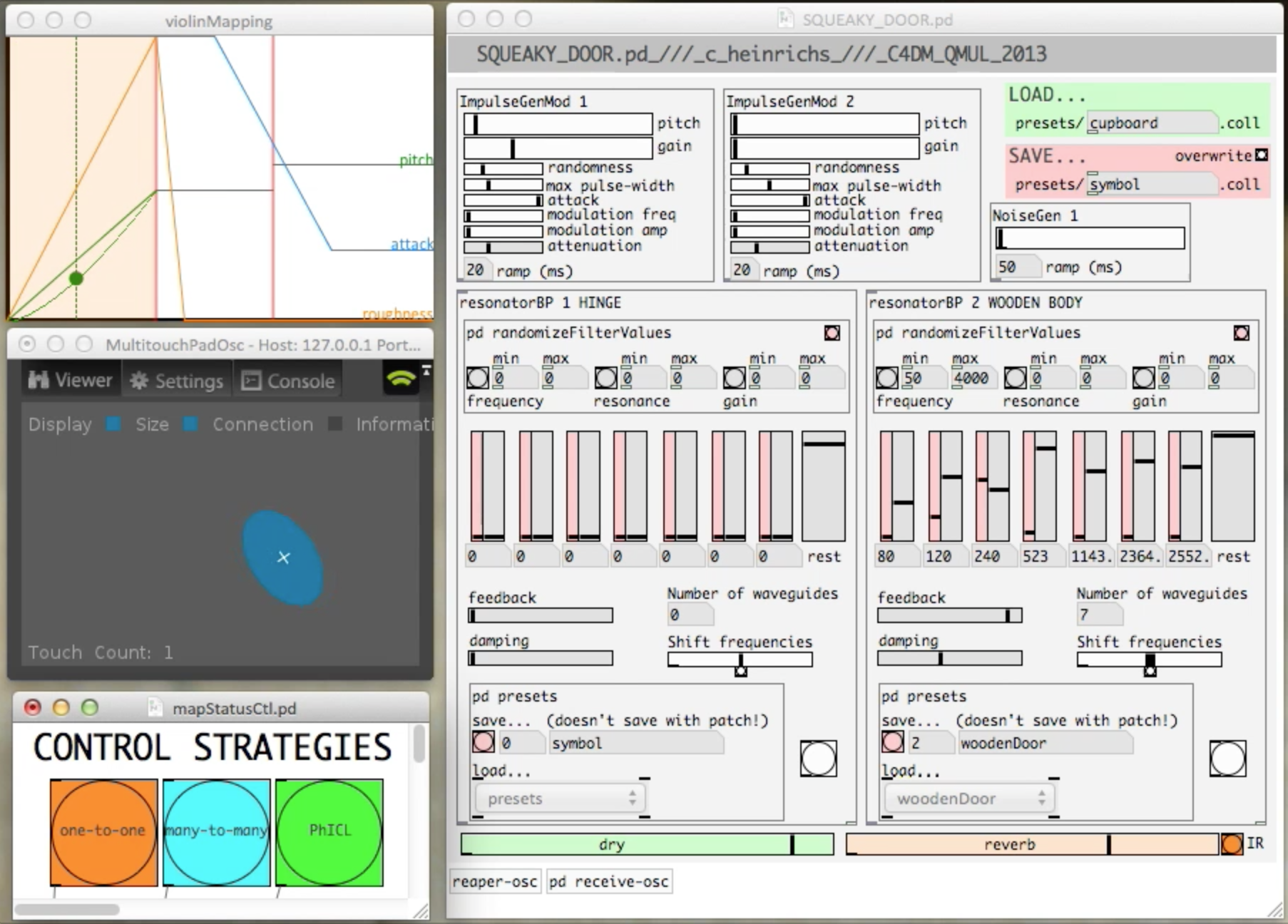

Design & Control Strategies for Performing Creaking Door Sounds

In the first study we have developed a model of a creaking door. The model’s parameters were based on subjective acoustical features (e.g. ‘roughness’, ‘pitch’) rather than physical processes (e.g. ‘applied force’, ‘angular velocity’), providing a parameter space that is closer to musical synthesisers and more conducive to established mapping techniques for expressive performance. Three mappings were tested between a touchpad and our door creaking model. Among these mappings was our conception of a Physically Inspired Control Layer (PhICL), which uses a physical metaphor that shares properties with both the interface and the synthesis model as a means of providing more natural control. In this case we used the metaphor of a bowed string, where touch velocity, size and vertical position relate to physical parameters of a bow which in turn produce varying parameters for the creaking door model. This, along with more conventional one-to-one and many-to-many mappings were the subject of a detailed user study (see SIVE’14 workshop paper below).

Contrary to our expectations the PhICL received the worst ratings while the control layer based on arbitrary many-to-many mappings between touchpad and sound model parameters received the best ratings based on both quantitative analysis and questionnaire responses (followed closely by the one-to-one mapping). As participants only had a limited amount of time to learn how to perform sounds on each interface a possible explanation for these findings is that performers preferred mappings that provided the most access points for controlling an individual feature of the sound. Interestingly the ‘winning’ interface also produced the least believable sounds based on results from a listening study. This suggests that the interface that ‘feels right’ to the sound designer does not necessarily produce the best results from an end-user point of view.

Prosody and Asynchronicity in the Performed Synchronisation of Computational Audio to the Moving Image

In this study Foley artists and mixers were asked to perform the soundtrack (impacts, scrapes and squeaks) to a short film captured from a procedural animation system. The animations are of a wooden character whose limbs collide with and scrape along the floor as it walks, runs and attempts to jump over obstacles (see Figure 2). As the animations are based on a physical simulation it is possible to compare performed and automated soundtracks side by side. While both the synthesis method and the control interface are the same throughout all stages of the study, participants are given the opportunity to customize and get used to the sound models, so as to minimize any biasing effects of the interface and increase the artist’s confidence in the task.

Film theorists place a lot of emphasis on synchronisation as being a fundamental expressive channel. Most notably, Michel Chion proposes the existence of an audio-visual contract, whereby sound and image never perfectly coincide with one another, therefore letting the audio-visual image equate to something greater than the sum of its parts. It would therefore be surprising to not see any strong deviation between performed soundtracks and those generated by physical data. More interesting than if the performed soundtrack deviates is the question of how it deviates from physical realism. Is there any noticeable consistency in this deviation, and, if so, what would be some ways of representing this systematically? Analysis of logged data in conjunction with qualitative analysis of comments made throughout the synchronisation process will help shed light on these questions.

Digital Foley

Following on from findings and design principles developed in this research a separate project is underway with the working title of ‘Digital Foley’. The project is funded by Queen Mary Innovation and will undergo a second phase of development throughout 2017. The first phase of development consisted of a hardware kit and software prototype which was presented at industry-leading conferences including Game Developer Conference 2016 and AES Audio for Games 2016.

Publications

Heinrichs, C. & McPherson, A. (2016). Performance-Led Design of Computationally Generated Audio for Interactive Applications. Proceedings of the TEI’16: Tenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction. Eindhoven, Holland.

Heinrichs C., McPherson A., Farnell A. (2014). Human Performance of Computational Sound Models for Immersive Environments. The New Soundtrack, Special Issue: Perspectives on Sound Design. Edinburgh, UK.

Heinrichs, C. & McPherson, A. (2014). Mapping and Interaction Strategies for Performing Environmental Sound. 2014 IEEE VR Workshop: Sonic Interaction in Virtual Environments (SIVE). Minneapolis, MN.

Presentations and Workshops

Digital Foley: Leveraging Human Gesture in Game Audio. Game Developers Conference. 17 March 2016. San Francisco, CA.

Digital Foley: Leveraging Human Gesture in Game Audio. AES 61 Audio for Games. 11 February 2016. London, UK.

An Elephant Named Expressivity - Towards Performable Computational Sound Model. Procedural Audio Now! Microsoft Skype. 30 January 2014. London, UK.