I have investigated the potential of using continuous key position as an expressive control in keyboard-based digital musical instruments, and how this relates to some “analog” instruments such as the Hammond organ and piano. You can find more about it in some of my publications:

- PhD thesis: Beyond key velocity: continuous sensing for expressive control on the Hammond organ and digital keyboards

- NIME 2020: A Platform for Low-latency Continuous Keyboard Sensing and Sound Generation

- JASA 2017: Dynamic temporal behaviour of the keyboard action on the Hammond organ and its perceptual significance

What follows is a summary of how I started becoming interested in these topics back in 2015, but the conclusions of the work can be found in the publications above.

When a keyboard player strikes a note, the temporal evolution of the key position is much more complicated than we may expect and is influenced by a number of factors. If the finger was touching the key before pressing it (pressed touch), you would probably see a progressive increase in the key velocity. If the key was already moving as it engaged the key (struck touch), the velocity would spike at the beginning and then slightly decrease during the remainder of the key onset. Looking at a keyboard player playing one key with one of the two types of touch above will immediately tell you that they are different, the body and hand movement can be drastically different. Your piano teacher would stress on the importance of using the appropriate type of touch for the piece or the note you are playing. Studies have shown in how many different dimensions a performer can control their gestures, and also that the gesture in use will have some direct impact on the sound produced: your piano teacher was right.

Yet, over thirty years of digital keyboard controllers made us used to think that the only thing that matters in a key press is how fast we press a key. While it is easier to produce slow notes with a pressed touch and fast notes with a struck touch, both types of touch can be used to produce a wide range of key velocities. In fact, the distinction between pressed and struck touches is not sharp, the two macro gestures blur into each other with infinite intermediate possibilities. Reducing the arbitrary temporal evolution of the key position to a scalar velocity parameter has long been accepted in instrument design as sufficient for most applications, a choice perhaps conditioned - or conditioning - the velocity-based encoding of notes chosen by the MIDI standard.

So what about the original intent of the performer? What do we make of their piano teacher’s yells? Is that going to get lost? With the increasing number of great digital keyboard controllers on the market, paired up with hyper-realistic audio engines, what are we going to do with hundreds of years of disciplined training at a grand piano keyboard? Will it all get lost in velocity?

Something actually did get lost in pipe organs. Pipe organs are not velocity-sensitive in the traditional sense: the speed of a key press is not going to affect the loudness of the produced tone. Yet, a performer at the pipe organ can shape the attack of the note according to the temporal evolution of the key position during the key onset. Or at least, they can do this on organs with a tracker action. By slowly depressing the key, they can let the air flow into the pipe gradually, so that the sound builds up slowly, while pressing the key in a single, quick motion provides a sharper attack. Such organ actions are progressively being abandoned in favour of cheaper and more flexible electro-pneumatic actions, which do not allow this degree of control, to the discontent of performers. Again, the subtle control does not allow the performer to change the loudness of the sound, but it positively affects the phrasing and the texture of the work. A small, almost unperceivable phenomenon on its own, which has a great influence on the overall result.

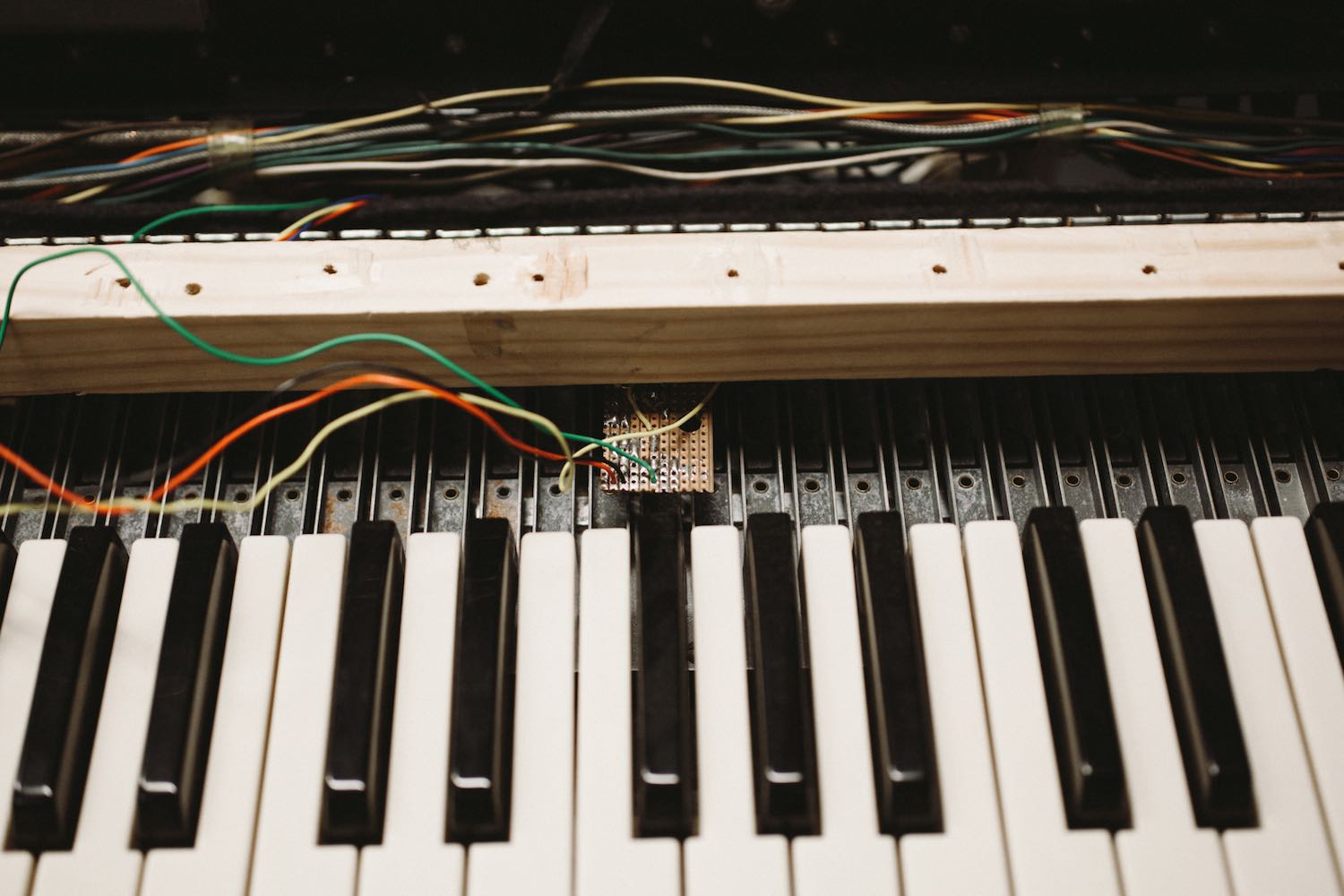

I have looked into the effect of the touch on the Hammond organ. An iconic instruments of the 20th century, dragged from the churches to the jazz clubs at first, and to rock arenas later on, weighing in at over 100kg, the Hammond is a hard-wood cabinet filled with vacuum tubes and a spinning engine, which all add up contribute to its unique sound. Its keyboard action is such that, for each key press, nine switches, each carrying one of the harmonics of the note, are closed at different points in the key travel. This action allows to obtain partial pitch-less key presses, for percussive effects, and also to gradually fade in harmonics, one at a time. Another consequence of the action is that each note on the Hammond organ is preceded and followed by transients, associated with the closing of these contacts: the “key-click”. Despite not being an intentional design feature in the mind of Mr Hammond, the key-click is one of the key signature sound features of the Hammond. We use Bela as a data-acquisition device on a 1967 C-3 Hammond organ, to sense continuous position of the key and the state of the bouncing contacts, as they close during a note onset. It turns out that the performer can shape the key-click with different touch gestures, again quite a subtle effect, which may have implications on the overall result in a musical context.

The market is flourishing with digital clones of the Hammond, (sometimes) cheaper than the original instrument but - most importantly - easier to transport. And here we are, back at wondering whether a velocity-based keyboard can be enough to reproduce the feeling and control of the original instrument. Manufacturers have gone a long way, using three switches per key, instead of the traditional two, on digital controllers. Will this be enough? How much are we losing of the original instrument, while trying to approximate it? What are we willing to exchange for cheaper and simpler designs?

From a broader and less Hammond-centric perspective I have also studied how different mappings of the continuos key position to the generated sound affect the experience of the performer and how they can be used as performance controllers. At some point I will get the time to write about it here and in a paper, in the meantime check out chapters 4 and 5 of my thesis.