June 17, 2024

AIL Open Seminars #005

Join us for the latest in our AIL Open Seminars series! This talk will be hybrid, in-person at Imperial College London (Dyson School of Design Engineering) and live-streamed on our YouTube Channel.

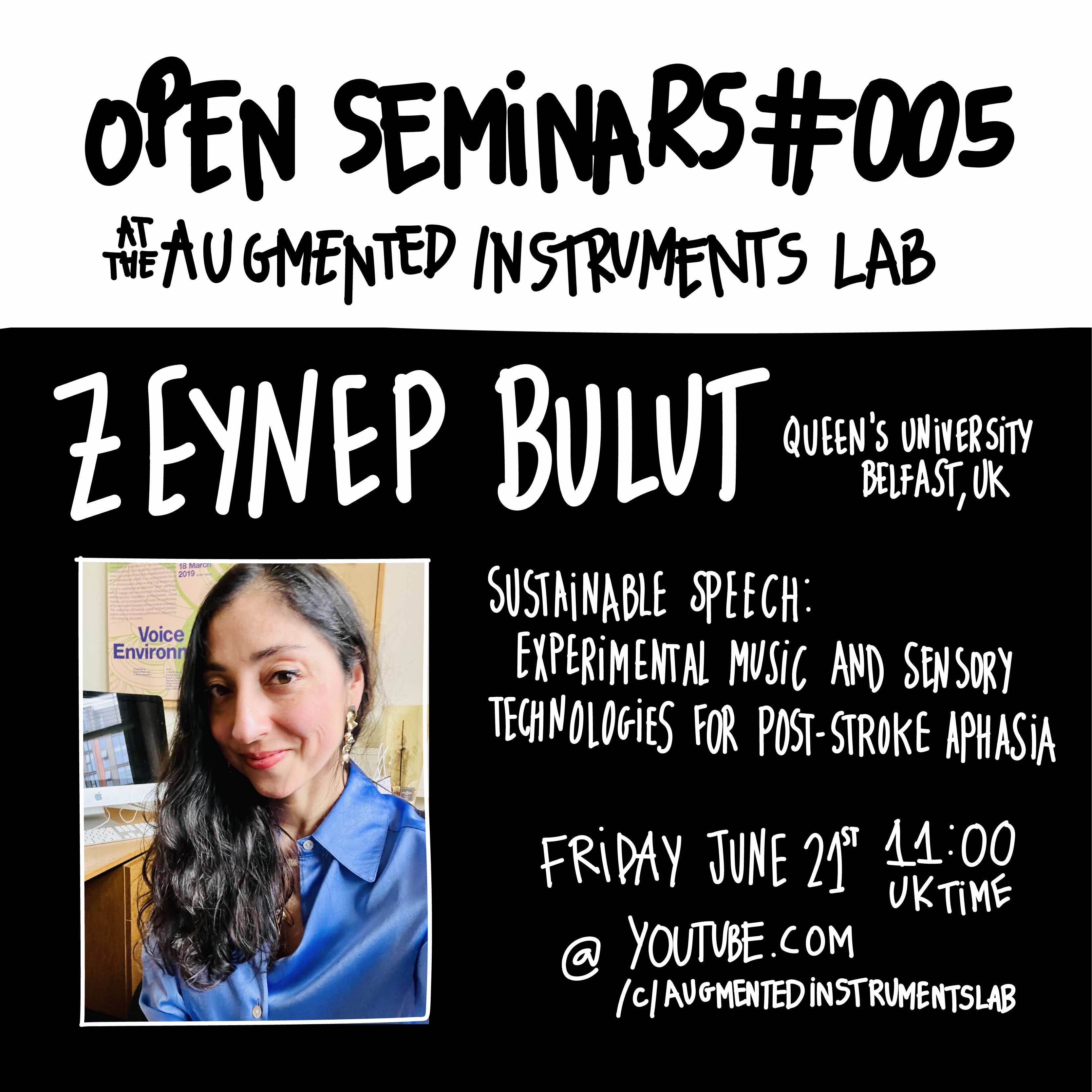

For this seminar we are excited to welcome Zeynep Bulut, a voice and sound theorist and a Lecturer in Music at SARC, Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Sound and Music, at Queen’s University Belfast. Her first book, titled, Building a Voice: Sound, Surface, Skin (London: Goldsmiths Press, 2024), explores the emergence, embodiment and mediation of voice as skin. Her articles have appeared in various volumes and journals including The Oxford Handbook of Sound Art, Perspectives of New Music, Postmodern Culture, and Music and Politics. She is project lead for the research platform, Music, Arts, Health, and Environment, supported by the Economic and Social Research Council’s Impact Acceleration Account at QUB. Alongside her scholarly work, she has also exhibited sound works, composed and performed vocal pieces for concert, video, and theatre, and released two singles. Her composer profile has been featured by British Music Collection. She is a certified practitioner of Deep Listening.

This talk draws on Bulut’s larger research project, titled, Sustainable Speech, which has been supported by the Engaged Research Seed Fund at Queen’s University Belfast.

Title: Sustainable Speech: Experimental Music and Sensory Technologies for Post-Stroke Aphasia

Time: 11am UK time (GMT+1), Friday, June 21st, 2024

URL: YouTube Livestream

If you are in London and would like to join in-person please email l.morrison@imperial.ac.uk for directions

Abstract

In this talk, I will discuss the notion of sustainable speech drawing on digital and sensory technologies devised for post-stroke aphasia together with the conceptions of embodied voice in experimental music. By sustainable speech, I refer to empowerment to speak both within and beyond the bounds of language, rather than a linguistic, semantic or vocal fluency. Cognitive psycholinguistic and functional approaches describe aphasia as a “breakdown of information processing and linguistic abilities” deriving from a brain injury or trauma (Valletta and Barrett 2018). In a different context, amid social traumas, disintegration and mobility, early to mid-twentieth century avant-garde and experimental music practices employ the breakdown of language as a social commentary and an aesthetic modality. Whilst performing a metaphor and abstraction, the breakdown of language in these practices underlines the malleable, embodied, and cross-sensory aspects of voice and language, and leads to an ecological understanding of speech. This ecological understanding, I argue, expands on both verbal and non-verbal forms of expression, and provides critical and creative tools for dismantling the normative limits of linguistic, semantic and vocal fluency as well as the notion of rehabilitation for functional speech.

In pursuit of this idea, I will cross-read creative and functional technologies employed for recovering speech and language, including digital voice assistants, smart phone and tablet applications, wearable electronics and assistive music devices. I will address some of these technologies (such as the TactusTherapy, Cuespeak, Throat Sensors developed by John Rogers at Northwestern University, and Soundbeam) in conversation with text and graphic scores, and tape and gesture-based performances in experimental music practices (such as Pauline Oliveros’ Sonic Meditations, and Mark Applebaum’s composition, Aphasia). With this cross-reading, the suggestion is to examine the ways in which experimental music practices may recover speech as an ongoing, open and changeable experience, in line with what scholar Jonathan Sterne calls, “impairment phenomenology” (Sterne 2021), and, whether or how “data-driven” devices such as the wearables and assistive music technologies can prompt “an art of living,” and a “technology of the self.” (Schüll 2019, DeNora 2000).